I went through several water treatment methods on the PCT. I tried:

- Filtering with a Sawyer filter from a Sawyer water bag into a water bladder in my backpack.

- Treating my water bladder with MSR Aquatabs rather than filtering.

- Carrying dirty water in SmartWater bottles, and drinking directly through a Sawyer filter.

I thought the last one was by far the best approach, and I observed most thru-hikers generally settled on it too. Here’s a comparison of water carrying and treatment methods which, I think, will explain why:

In Short:

Drinking through a Sawyer Squeeze filter from a SmartWater bottle requires virtually no downtime, allows cameling up, and tastes good. Drinking pre-treated water from a water bladder is a little more convenient while you’re moving, but requires a lot of downtime, and encourages you to carry too much water. Tablets are a very good idea as backup, since filters do fail and tablets weigh almost nothing. But, they don’t taste good, and require you to carry water you can’t drink for a while, effectively increasing your pack weight.

Since pack weight is so important, and water is heavy, the method that lets you carry the least water is the best. The fact that it tastes good and allows less downtime around mosquitoes is icing on the cake.

Additionally, I suggest swapping the Squeeze’s mouthpiece with one from a 700ml SmartWater “sport” bottle, and carrying a scoop/cup to aid in water collection from awkwardly-shaped water sources.

In Long:

When to Treat:

If you use a water filter, you can either treat your water at the when you collect it, and carry clean water, or you can carry dirty water and drink straight through the filter. Here are the pros and cons of each:

Filter at the Water Source Pros:

- The Sawyer directions suggest this approach.

- If you want a rest anyway, you can do something productive while resting.

- Certain carrying methods require this (e.g. unless you use an inline filter, having a water bladder in your pack requires pre-treated water).

- Allows you to give more attention to the water being filtered. E.g. you can watch for clumps of algae more easily.

Filter at the Water Source Cons:

- Takes a long time.

- You need to carry separate water vessels for clean and dirty water.

- Some water sources are unpleasant places, particularly due to mosquitoes. Standing still is the last thing you want to do near mosquitoes.

Drink Through the Filter Pros:

- Takes virtually no time at most water sources.

- You can rest when you want, rather than having to rest at water sources.

- You can “upgrade” your water if you find a nicer source soon after a dirty one, avoiding unnecessary clogging and improving flavor.

- My sister won’t complain about how long you’re taking at water sources.

Drink Through the Filter Cons:

- As the filter clogs, it will get frustratingly slow to drink.

- You need to tip the water bottle up while you drink, which makes it hard to look at the trail, which increases the risk of tripping.

Carrying Vessels:

Water Bladder Pros:

- Convenient to drink from. You won’t dehydrate yourself just because it’s inconvenient to reach your water.

- Places all your water right next to your spine, which can be good for pack balance.

Water Bladder Cons:

- Refilling requires emptying and re-packing your pack. When I used a Sawyer filter and a water bladder, a complete fill-up took me 10-15 minutes. Because of this, you will do longer water carries than you need, effectively adding pounds to your pack.

- Water bladders can’t freestand, making refilling them precarious. Awkwardly balancing the flexible sides between your knees will become an everyday anxiety. Expect to have it tip over and empty out all of your painstakingly filtered water a few times.

- Can develop leaks at stress points, which you probably won’t notice until your water is unexpectedly gone and your pack is wet.

Sawyer Bag Pros:

- It comes with the filter and the directions say to use it.

- ???

Sawyer Bag Cons:

- Awkward shape doesn’t fit in most pockets when full.

- Notorious for developing leaks near the neck, which makes it impossible to maintain pressure and therefore to treat your water.

- Somewhat soft-sided, so it can collapse and spill easily.

- Difficult to fill if falling water is unavailable. Without rigid sides, it won’t fill up when you submerge it in standing water. You can fill it by yanking it back and forth, but this stirs up silt that will clog your filter.

- Opaque, so you can’t see if you picked up debris that will clog your filter.

SmartWater Bottle Pros:

- Cheap, durable, and easy to replace.

- Free-standing.

- Fills quickly. Collecting water takes almost no time at all, you just reach down and fill up.

- You can cut one down to make a cup/scoop, for gathering water from awkwardly-shaped water sources. You can also cover the scoop with a bandanna when collecting water from very poor quality sources, to pre-filter out larger debris, which helps your filter last longer.

- The tall and skinny 1L size fits well in most backpack side pockets.

- Easy to expand carrying capacity — just stuff more bottles wherever they’ll fit.

SmartWater Bottle Cons:

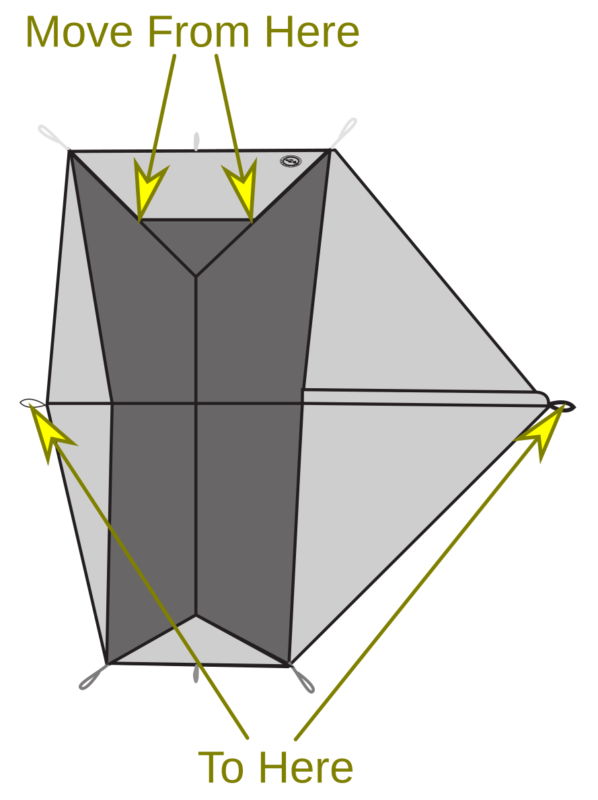

- Backpack side pockets are not always easy to reach. I had to rearrange the contents of my pack to make it easier to slide my water bottles in and out of the side pockets.

- They won’t fit in some shallow or narrow water sources (if that happens, use a scoop to collect, use your trowel to dig the source deeper, or check upstream/downstream for an easier collection point).

- When drinking from a directly-attached filter, you need to periodically disconnect and reconnect the bottle to let air in and equalize the pressure.

- They look like they should leak after the wear and tear of daily trail use (but, they don’t).

Treatment Methods:

Sawyer Squeeze Pros:

- You can camel up. If you drink 1L while you’re at the water source, that’s 2.2lbs you don’t need to carry.

- High flow rate.

- Takes a long time to clog, so long as you take reasonable care of it.

- The water tastes like water.

Sawyer Squeeze Cons:

- It you allow its temperature to get below freezing, water retained in the microscopic tubes within can freeze, which can cause the tubes to rupture. This will make it ineffective at filtering out pathogens, and there is no way to tell until you get sick. Take it inside your tent on nights that might drop below freezing. Replace it if you think it might’ve frozen.

- A little leaky where it screws onto the dirty water bottle.

- The rubber grommet that seals the connection to the dirty water bottle can be damaged from overtightening, greatly increasing dirty water leakage. It will take some experience to learn how tight is just right. You may ruin a grommet or two in the process — perhaps carrying spares would be a good idea (I didn’t, but I’d used these filters for a long time before my hike).

- The factory mouthpiece is inconvenient and requires two hands — and those hands probably have dirty water on them. I recommend swapping it for the mouthpiece that comes on Smartwater 700ml “sport” bottles, which is much more convenient and has compatible threads.

- Requires periodic backflushing to keep the flow rate good.

- Will eventually clog up, but with enough backflushing this can take a very long time. (The packaging’s claim that it can treat a million gallons is ridiculous, however — consider this a consumable item, like shoes).

Sawyer Mini Pros:

- 1oz lighter than the Squeeze, but still treats all the same pathogens and allows cameling up.

- The more angular shape makes it harder for dirty water to dribble into your mouth from a bad seal.

- Mouthpiece is more convenient than Squeeze’s factory mouthpiece (but is not replaceable)

Sawyer Mini Cons:

- Much slower flow than the Squeeze. It’s frustrating to drink from when you’re thirsty and walking. Get used to looking down at the trail out of the corner of your eye while drinking.

- Clogs much faster than the Squeeze. I managed to get one to last 900 miles, but this is highly unusual. I pre-filtered dirty water through a bandanna into a scoop to slow clogging, and I thoroughly backflushed at nearly every resupply. It was still agonizingly slow near the end.

- Grommet can be damaged more easily than the Squeeze.

- Everything form the Squeeze

MSR Tablet Pros:

- Even lighter than a Mini

- Faster than chlorine tablets

- Less work than filtering into a clean bottle/bladder

- They weight basically nothing and can treat any pathogen you’d find in PCT water. I strongly recommend carrying these as a backup for your Squeeze, in case the Squeeze freezes, gets dirty water on the clean side, or is otherwise compromised.

MSR Tablet Cons:

- Can’t camel up, effectively adding pounds to your pack during wetter sections of the trail.

- Supposedly requires you to shake the water for the first 10 minutes of treatment to be effective.

- Each tablet treats 2L, which is an inconvenient size — bottles are usually 1L, and bladders are usually 3L. You can break them in half, but it’s hard to do cleanly.

- Water tastes like treatment chemical (but, not nearly as bad as iodine or chlorine tablets).

- Takes 40 minutes before you can drink, which is agonizing at times.